Novel long-read sequencing workflow developed for use in routine cancer diagnostics

Bridging the gap between medical research and clinical laboratories is often perceived as a major challenge in healthcare. Clinical laboratories are interested in using the latest medical research technologies to aid patient diagnosis and treatment, but more mature technologies are often used as a routine. This occurs primarily because integrating new technologies into a clinical laboratory setting can be time-consuming, costly, warrant new instrumentation, require staff training, and necessitate additional logistics solutions. However, the rapid implementation of novel technologies into clinical practice is important, especially in cancer research.

Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) is a well-studied cancer type that affects white blood cells and tends to have a slow progression. Whilst multiple efficient drug treatments are available, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), some patients develop drug resistance. The mechanism behind this drug resistance is not always known, but research has shown that many of these patients have point mutations in the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene, which is the gene that TKIs target. The same gene has also been implicated in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) drug resistance.

To date, identification of the mutations in BCR-ABL1 that are related to drug resistance has usually been done using Sanger sequencing, which has limitations. The use of other research technologies, such as next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques, could prove valuable in cancer diagnosis and treatments. One of these NGS techniques, called long-read single-molecule sequencing (LR-SMS), could help clinicians to determine the clonal distribution of mutations, and to read through and identify previously uncharacterised structural variations. However, until now, efforts to implement LR-SMS in routine clinical diagnostics have been hindered both by the lack of computational and bioinformatics resources, and the lack of established workflows and tools for organising as well as automating the analysis work needed for LR-SMS.

In a recently published article in Cancer Informatics, researchers from Uppsala University and Uppsala University Hospital (First author: Wesley Schaal, Corresponding author: Ola Spjuth, Uppsala University/SciLifeLab) implemented long-read sequencing for BCR-ABL1 TKI resistance mutation screening in a clinical setting for patients undergoing treatment for CML.

Previous work has shown that LR-SMS can be applied to studying BCR-ABL1 mutations in CML patients (Cavelier et al. 2015). Schaal and colleagues now report the development of a fully integrated pipeline using long-read sequencing at an academic facility to aid clinical decisions in the hospital. Firstly, RNA from bone marrow or blood samples was extracted from cancer patients with suspected drug resistance (CML=36 and ALL=3), and long-range PCR amplification of the BCR-ABL1 transcript was performed on the samples. Circular consensus sequence (CCS) reads in FASTQ format were then generated for each sample and used as input for the automated analysis pipeline.

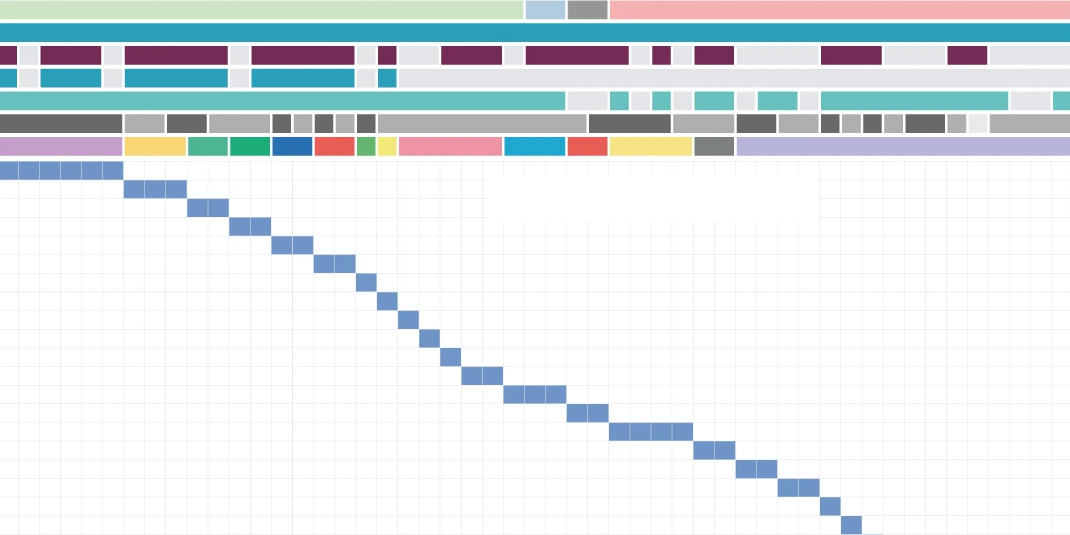

In brief, the pipeline consisted of seven steps. The first step was filtering. As the researchers aim was to study the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene regions, they filtered the BCR-ABL1 fusion reads from reads from ABL1 (not fused with BCR). Only BCR-ABL1 fusion gene reads were then used for further analysis. In the second step, a reference sequence was assigned. The third step was a quality control, performed to ensure that no mutation sites are missed. In the fourth step, the search for novel unreported mutations began, with the reads being compared to the reference sequence. In the fifth step, all previously known and potentially novel TKI resistance mutations in the BCR-ABL1 were analysed and variant allele frequencies (VAF) were determined. In the sixth step, clonal composition of positive mutations was determined. In the final step, all results were collected in a local database. In addition, raw data files, quality control data, and mutation results were stored in a custom-made information system.

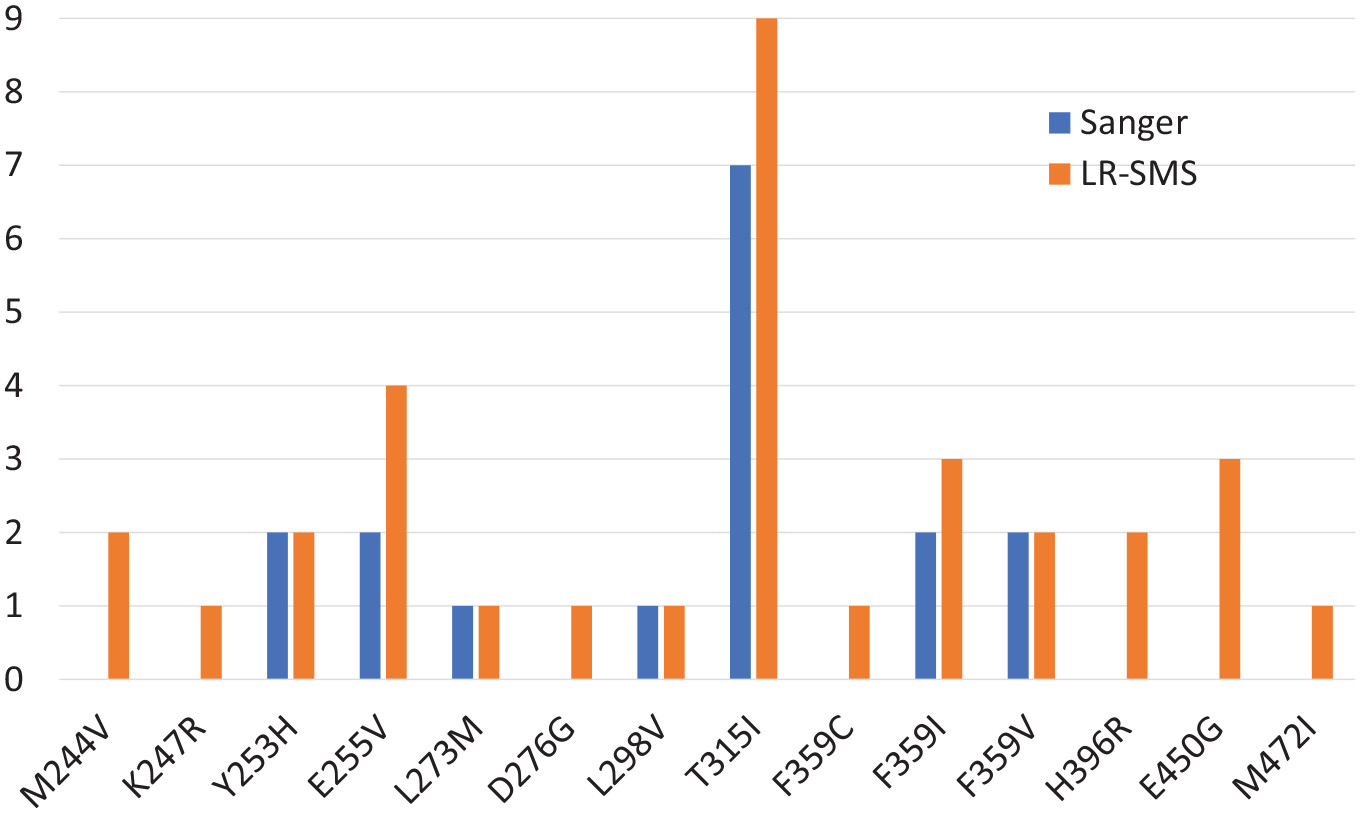

Using the pipeline, the researchers were able to compare the results from long-read sequencing with traditional Sanger sequencing, which is used as the routine method at Uppsala University Hospital. Validation checks confirmed that all 17 resistance mutations found by Sanger sequencing were also detected by long-read sequencing. Notably though, 16 additional de novo mutations were found only by long-read sequencing. All of these mutations had frequencies below the detection limit for Sanger sequencing. The new pipeline was found to detect all cancer mutations occurring in frequencies higher than 1%. In summary, long-read sequencing was found to have higher sensitivity, and be able to detect emerging TKI resistance mutations earlier than Sanger sequencing.

After implementation and validation, the clinical laboratory at Uppsala University Hospital changed their method, and now uses long-read sequencing for this application. One important factor behind the switch was the user-friendly pipeline information system. The system is comprised of features for data management, analysis, and visualisation, and thus faciltates the use and interpretation of the data by clinicians.

Data and code availability

In accordance with the principles of Open Science, the researchers have made the software developed in the study available open source on GitHub: https://github.com/pharmbio/clamp. All FASTQ files are automatically processed through a collection of custom scripts written in R and Perl.

Article

DOI: 10.1177/11769351221110872

Schaal, W., Ameur, A., Olsson-Strömberg, U., Hermanson, M., Cavelier, L., Spjuth, O. (2022) Migrating to Long-Read Sequencing for Clinical Routine BCR-ABL1 TKI Resistance Mutation Screening. Cancer Informatics 21.

Funding

This project was funded by the Swedish strategic research programs Swedish e-Science Research Center (SeRC) and eSSENCE. All LR-SMS sequencing was performed by the National Genomics Infrastructure (NGI) Uppsala, which is hosted by Science for Life Laboratory (SciLifeLab).