Bayesian deep learning model finds clues about the evolution of open habitats

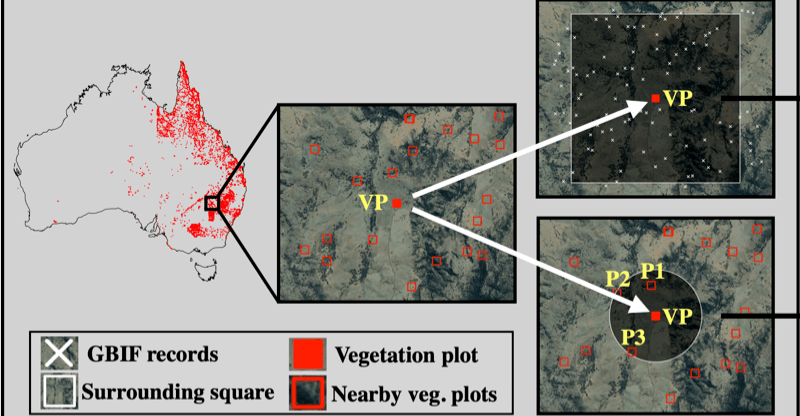

Courtesy Tobias Andermann, Uppsala University.

All species on Earth, including terrestrial animals, interact and evolve on the biotic landscape. The biotic landscape comprises different types of vegetation and their spatial distribution. Researchers have performed reconstructions of past vegetation, so-called paleovegetation, at a number of specific sites based on the fossil remains of plants found in the sediment. This has yielded evidence that vegetation does not remain static. Rather, it changes and evolves over time, for example in response to changes in climate. The emergence and expansion of open habitat grasslands is perhaps the most remarkable case of major vegetation changes in recent Earth history. Today, open vegetation, like temperate grasslands and tropical savannas, covers over 40% of the Earth’s land surface. However, these biomes likely did not exist in this form about 30 million years ago (half of the time-period since the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs 66 million years ago). At that time, the surface of our planet looked different, likely mostly covered in forest, and none of the creatures roaming the Earth had ever experienced the sight of vast open grasslands. It is only in the last 30 million years that grasslands expanded and many mammals became adapted to a grazing diet; coevolving with this new biome type.

The dynamics of when open grassland originated and began to expand are not fully understood and are the subject of debate. Previous studies aiming to explore changes in past vegetation have used climate-based models and predefined tolerance limits for certain biome types. However, information related to mammal-plant interactions, such as the presence of grazing mammals being an indicator for the presence of open habitat grasslands, has not been systematically applied in these models. To date, information about these interactions is only used to infer paleovegetation at individual fossil sites. Mammalian fossils have also, at times, been used to validate vegetation predictions produced using climate-based models. Whilst a large number of mammalian fossil datasets are publicly available online, no computational models have utilised these openly available datasets to predict past vegetation.

In a recent publication in Nature Communications, Tobias Andermann (SciLifeLab/Uppsala University) and colleagues from Sweden, the US, the UK, and Switzerland presented a Bayesian deep learning model to improve modelling of past vegetational environments. Their Bayesian deep neural network (BNN) model uses comprehensive information from multiple sources, such as mammalian fossils, geological models, modelled paleoclimate and elevation estimates, and spatial and temporal coordinates, including tectonic movement, to reconstruct paleovegetation.

First, Andermann et al. (2022) trained the model using independent vegetation datasets that included information related to both modern vegetation and paleovegetation (North America; 300+ independent points with reconstructed paleovegetation throughout last 30 million years). The researchers then added information about mammal-plant interactions, available in public databases for paleobiology and Cenozoic angiosperms, for different mammal and plant taxa. They also complemented the training dataset with information from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) to provide the current occurrences of the animal and plant taxa involved. The presented Bayesian deep learning model does not require information on temperature tolerance limits or ecological interactions, but instead infers these interactions during training with the raw occurrence data. Once the model is trained, it can estimate (including uncertainty) the most likely vegetation for any given point in time and space.

Andermann and colleagues then applied the Bayesian deep learning model to infer past vegetation changes. The researchers aimed to determine how open vegetation expanded in North America throughout the last 30 million years. The results from the model showed that open habitats in North America first occurred around 23 million years ago. Open habitats already covered more than 30% of North America and were expanding when the Quaternary glacial cycles started about 2.5 million years ago. Today, open vegetation is the most prominent natural vegetation type found in North America.

In summary, Andermann and colleagues used an entirely data-driven approach to explore paleovegetation, in particular the origin and expansion of open vegetation. They showed that their Bayesian deep learning model was able to use fossil evidence as a basis for animal-plant interactions. The model, once trained, could then use this information to model how the vegetation changed over millions of years. This allowed the researchers to study how and when the biomes in North America changed from forests to open vegetation, such as savannas and open grasslands, over the last 30 million years. The results constitute a major step towards understanding how open habitat grasslands evolved over time and provide valuable new insights into the evolution of Earth’s biomes.

Data

In adherance with the open sharing of data and code, the researchers have shared the code for the BNN model, and also provided the main BNN functionalities as an open source Python package. This package can be used for any classification or regression task; it is not restricted to vegetation prediction.

-

All code used in this study, as well as a full data tutorial and installation instructions for training BNN models are available on the project’s GitHub repository.

-

Main BNN functionalities can be loaded as a stand-alone and open-source Python package, which is available on GitHub (v0.1.12 is the most current). This enables the described BNN approach to be applied to any classification or regression task, not just the task of vegetation prediction.

-

Supplementary data is available in Zenodo.

Article

Andermann, T., Strömberg, C. A. E., Antonelli, A., Silvestro, D. (2022). The origin and evolution of open habitats in North America inferred by Bayesian deep learning models. Nature Communications 13, 4833. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32300-5.

Funding

This research was funded by the SciLifeLab & Wallenberg Data Driven Life Science Program (KAW 2020.0239), Swedish Research Council, Swiss National Science Foundation, Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (FFL15-0196), United States National Science Foundation (EAR-1253713), and the Royal Botanic Gardens (Kew).